A foreign Frenchman in Grasse

- Tom Richardson

- Jul 31, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 15, 2025

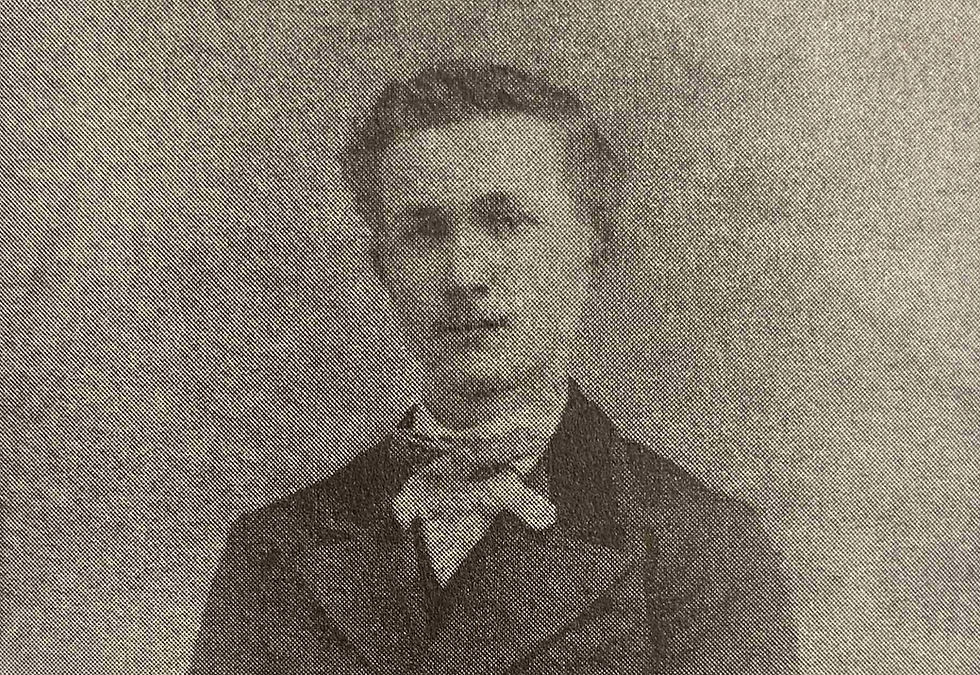

A Grassois by the distinctly non-Provençal name of Émile Litschgy (1920-2004) wrote three books about Grasse’s past. They aren’t really history, more a series of stories, but one* is about his grandfather of the same name, who came to Grasse aged nineteen in 1873 from a small potash mining town named Ensisheim, near Mulhouse in Alsace – hence his Germanic-sounding surname.

When Émile was born, in 1854, Alsace was part of France. But in 1873, when he arrived in Grasse, his birthplace had been German for two years. After the defeat of Napoleon III by the Prussians at Sedan in 1870, the residents of Alsace were in May 1871 given fifteen months to choose between leaving the region and remaining French or staying and becoming German.

Many took the first course – in fact a substantial number went to Algeria, which was already governed as part of France. Ominously for the country's politics, one individual who moved was the future Captain Alfred Dreyfus, most of whose family went to Paris in 1872 when he was thirteen. But in 1871, eighteen year old Émile was an apprentice confectioner in his home town. His mother decided that he should finish his apprenticeship and only then leave Alsace.

He went to Grasse in 1873 when he was nineteen, helped by an aunt in Marseille to find a job, but by then it was too late: as far as the French state was concerned, he was Prussian. Despite not understanding Provençal and rather bewildered by his unfamiliar surroundings, he went to work as a confectioner for a widow whose shop was in the Place aux Herbes.

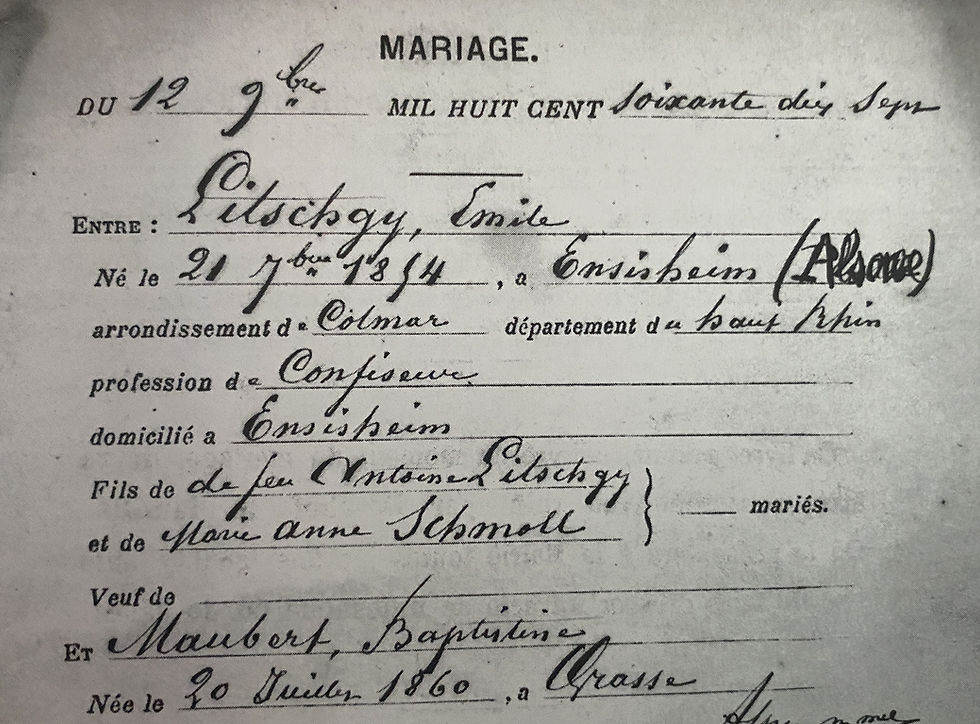

The widow had a daughter named Baptistine. Émile was clearly a very good worker, because with her mother’s approval, Baptistine married Émile in 1877. On his marriage certificate, his place of birth was registered as ‘Ensisheim (Prusse)’ (Prussia). Someone, probably Émile himself, has altered that to ‘Alsace’, but officially the French-born Émile is German.

The photo below shows the site today of Émile's family business at 2 rue de la Pouost on the south side of the Place aux Herbes. Known as the Appian House (after its builder), it's currently, as you can see, being very smartly refurbished. Émile had his kitchen behind the shop. His family, including his mother-in-law whom his grandson tells us dominated the business, lived above.

But his origin, marriage and long term residency did not affect his nationality as far as the French government was concerned. No less than ten years later, Émile received a document giving him official leave to remain in France (in modern terms, he was issued with a Carte de Sejour), although his birth place is now only given as Haut Rhin without specifying a country.

So he remained an exile in his own country. His grandson says that, despite his marriage and the successful family confectionery business, he always felt alone, isolated and never welcomed by the Grassois.

Émile and Baptistine had three sons, Joseph, Jean (the father of the teller of the tale) and Léopold and one daughter, Marthe. In 1890, when Joseph was eleven years old, the family suffered a disaster. The owner of their building refused to renew their lease and, worse, enabled someone else to establish a confectionery in Émile’s place. He was fortunate enough to find that his skills as a confectioner could be applied to perfume and was able to find a job at one of Grasse’s biggest businesses, Roure.

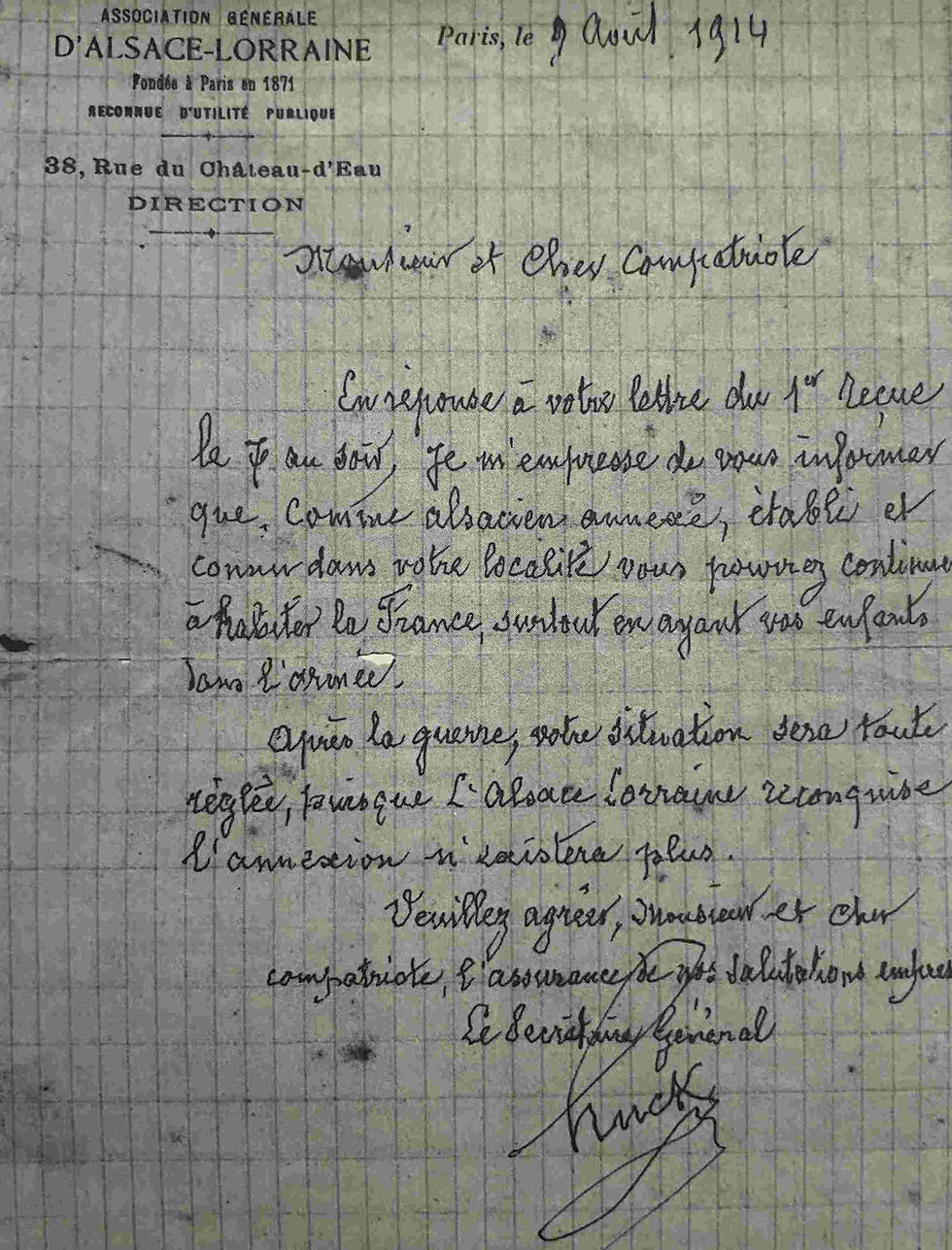

In 1901, his son Joseph was conscripted (by ballot) into the army: it seems that having a ‘foreign’ father did not exempt him. Although Joseph returned to civilian life in 1905, his brother Jean was conscripted in his turn, and when war broke out in 1914, all Émile’s three sons were mobilised. At the same time, German citizens living in the Alpes Maritimes were interned on the Ile Sainte Marguerite off Cannes. Could that happen to Émile? He was, no doubt, mightily relieved to receive this official letter from Paris to the contrary, although had he not been ‘established and known in your locality’, one wonders what might have been the outcome.

The text also shows the unwarranted confidence of the French government of the time that Émile is assured that his situation will be regularised after the war because France will recover Alsace-Lorraine! Since it is dated April 1914, it also shows that the government regarded war with Germany as inevitable at some time not much delayed.

Yet the insults continued: the military papers of all three of his sons were marked ‘fils d’étranger’ – son of a foreigner. Luckily, all three sons survived the war, although both Jean and Léopold were wounded.

After forty six years as a foreigner in Grasse, Émile finally became French again in 1919 when Alsace reverted to France (although not before there was a row between Clemenceau on the one hand and Wilson and Lloyd George on the other before the latter two rather grudgingly agreed).

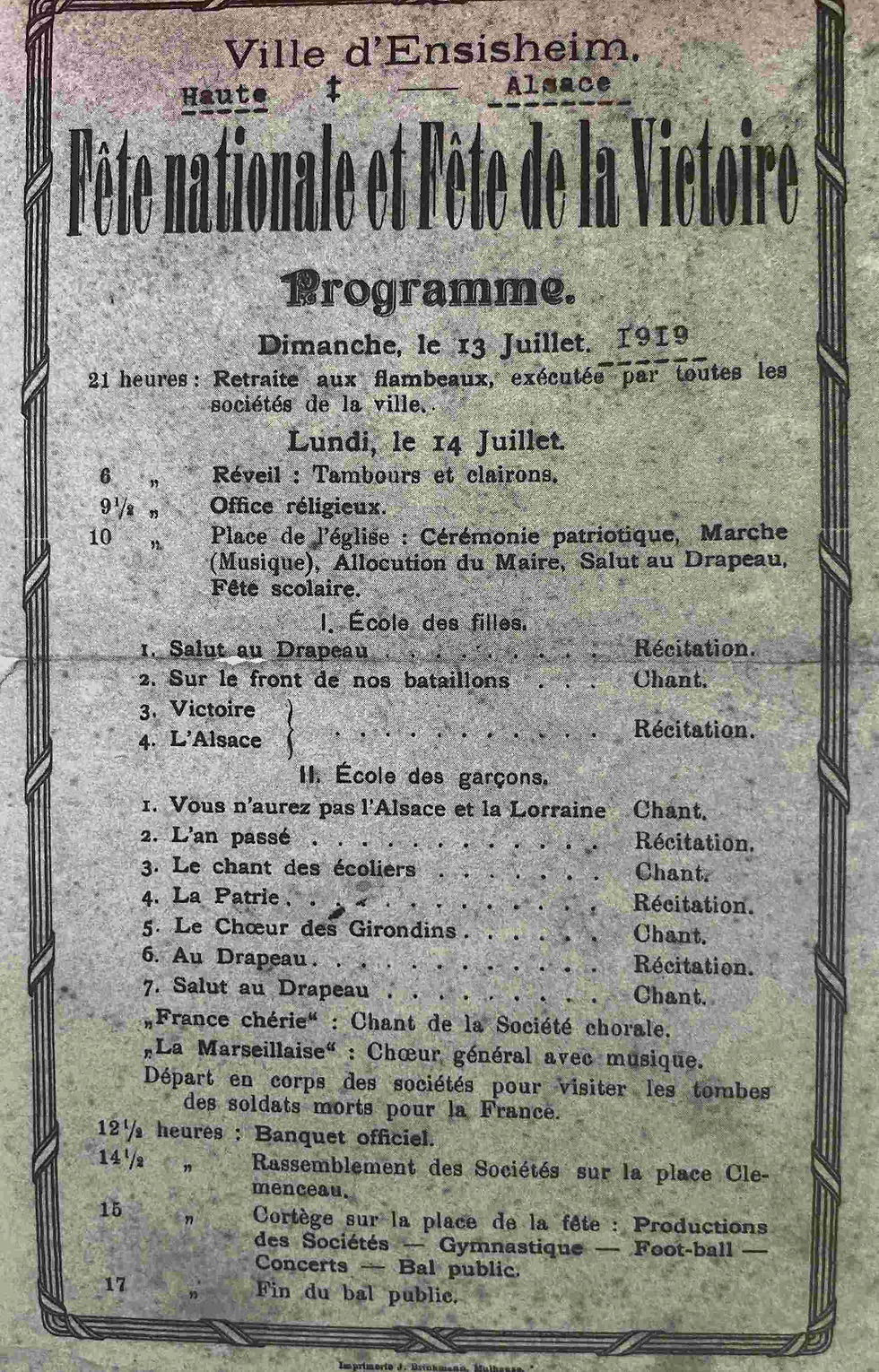

There appears to have been no official acknowledgment of his status, but amongst his papers,

his grandson found this carefully preserved poster dated 13th July 1919, celebrating a Fête de la Victoire (celebration of Victory) in his home town of Ensisheim. Fortunately, Émile didn’t live to see Alsace re-ceded to Germany, temporarily of course, in 1940.

We English have lived within virtually the same borders since the time of Athelstan in the tenth century and the island of Great Britain has been united since James I in 1603. Unlike mainland Europe, we have no experience of the idea that borders can move and nationalities with them. Such changes have most recently been far greater and more extensive in eastern rather than western Europe (and continue today), but we have been lucky to be an island!

*Émile Litschgy, 'On Lui Disait Maubert-la-Piece', TAC 1999

Comments