Grasse’s Fearless Street and two wartime episodes

- Tom Richardson

- Nov 7, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 30, 2025

There’s a short and very narrow street near the Porte Neuve with the odd name of rue Sans Peur (“Fearless Street”).

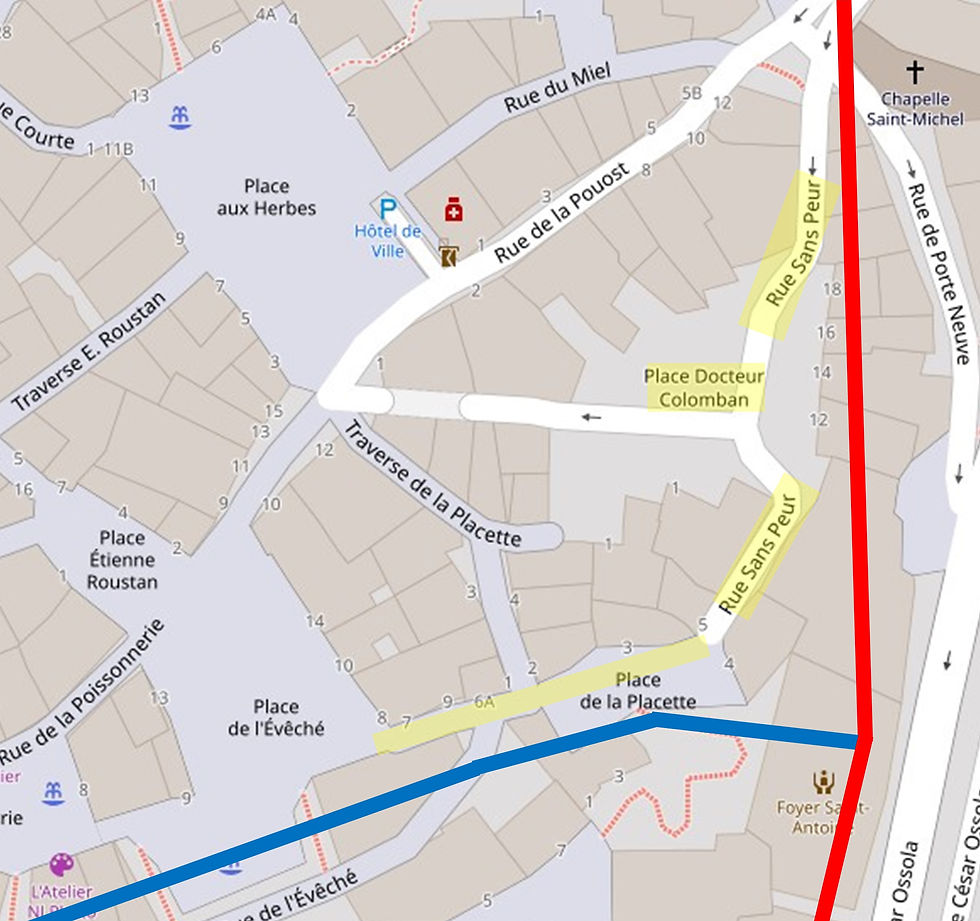

It was once twice as long as today, running through Place de la Placette towards what is now the Place de l’Eveche below the Town Hall:

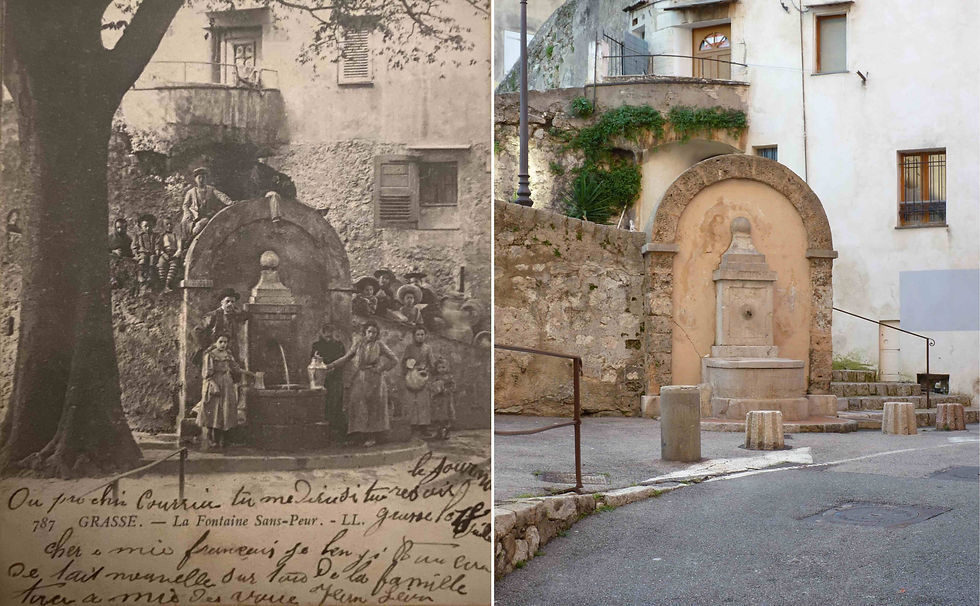

At the western end, it may originally have been a fosse (defensive ditch) outside the original eleventh century walls of the Puy, like Rue Tracastrel on the other side. Certainly, the north eastern part of the street abutted directly on to the fourteenth century wall. In the oddly named place de la Placette, the fountain retains the name 'Fontaine Sans Peur'. Here it is in a postcard from 1904 (written, rather charmingly, to the boss of a hairdressing salon in Paris). The tree apart, it looks little different now, but it would probably be difficult to find so many sitters today!

The image below shows what is now the remnant of rue Sans Peur as it looked before the Great War, perhaps somewhat sanitised for the photographer.

The story goes that the name arises because the inhabitants of the street helped the town’s garrison successfully to repel a besieging army led by the Count of Savoy in 1708. Both men and women are said to have thrown stones, buckets of ‘ordure’ and anything they could lay hands on at the besiegers. The rest of the townspeople rewarded them with the name ‘Sans Peur’.

As so often, the reality is more prosaic.

During the War of the Spanish Succession, the Austrians, British and others tried to restrain the expansion of France, then Europe’s largest and most powerful country, under Louis XIV. The war is best known in the UK for the successes of John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, most significantly at Blenheim in 1704 where his co-commander on the Austrian side was Prince Eugen of Savoy. (The Duke was a direct ancestor of Winston Churchill, who was born at Blenheim Palace.)

In 1708, the British and Austrians cooked up a strategy with another ally, Victor Amadeus, then Duke of Savoy which included Piedmont and Nice, to attack the main French Mediterranean naval base at Toulon. A combined army under Prince Eugen and Victor Amadeus marched along the coast via Antibes. It seems that they sent a small force to ensure there was no threat from Grasse on their flank to the north. It could not have been a real siege: had they really meant business, Grasse’s fourteenth century walls would hardly have lasted a day against eighteenth century artillery. They clearly decided that Grasse, and its unruly inhabitants, wasn’t worth their trouble, although they did extract a significant sum as a ransom to go away.

The ‘invasion’ got to Toulon but proved a failure because Victor Amadeus was no general and he, Prince Eugen and the admiral of the fleet providing the British contribution, the remarkably named Sir Cloudesley Shovell (did his nanny or his lovers call him ‘Cloudy’?), could not agree on how to work together. Poor Cloudesley came to a sad end, drowning on his return journey to England off the Scilly Isles along with three other ships and 2,000 sailors. Bad navigation, in an era before the development of the chronometer allowed accurate determination of longitude, got the blame.

Dr Pierre Colomban

The other episode is much more recent and deserves our respect. Rue Sans Peur was at the bottom of what had been Grasse’s Rouachier tanneries quarter and by the twentieth century living conditions were clearly pretty nasty, as this postcard shows.

In 1927, a building in the street actually collapsed, but nothing much appears to have been done until after the war ended, when this plaque commemorates what must have been one of the first examples anywhere of post-war slum clearance:

Pierre Colomban, who as a doctor with special knowledge of tuberculosis seems to have known the Rouachier quarter before the war, led a resistance group under the Vichy regime. When Vichy was terminated by the Germans in 1942 after the American landings in north Africa, Colomban was arrested by the collaborationist French Milice police. He was imprisoned by the Italians, who had taken advantage of the end of Vichy to occupy all of the Alpes Maritimes in addition to the slither they had annexed in 1940.

When Italy changed sides in 1943 after the fall of Mussolini, Colomban was able to escape from prison in Piedmont and after the liberation of Grasse he became first head of the liberation committee and then Mayor.

He must have taken almost immediate steps to address the problems around the rue Sans Peur because as early as 1947 “Place Doctor Colomban” had already replaced some of the slums. Unfortunately, he died that year at the early age of 50, perhaps due to his efforts during the war. It’s clear from the plaque that he was held in great respect by the townspeople.

There is not much to see there, but Place Doctor Colomban is quite an attractive little open space, much blighted, as usual today, by parked cars.

In the nineteenth century, the Place aux Herbes was created through the demolition of a large town house (a 'hotel particulier'). While the current focus in the old town is rightly on rehabilitating rather than demolishing buildings, Place Doctor Colomban does show that the judicious creation of new spaces has a part to play as well.

Brilliant! This - and some of your other stories - makes me want to have a guided tour of the old town (and it's watering holes). Are you available Tom?

Tom, you explain things in Grasse beautifully. I'm looking forward to my walking tour.