Grasse's Vanished Mansions

- Jan 10

- 7 min read

The period roughly from 1945 to 1973 is known in France as 'Les trente glorieuses' (‘the glorious thirty’) because of the economic growth and prosperity of the era. But it was also a time when the French population moved from the country to the towns and cities. In 1945, no less than 35% of the workforce was still agricultural, but by 1973 it had dropped to 9%. One result was a building boom – all those ugly fifties and sixties apartment blocks, block-like schools and public edifices apparently thrown up in a hurry. (The same occurred in the UK, but more to replace eighteenth and nineteenth century slums than to accommodate a movement from country to city: the agricultural population of the UK in 1945 was no more than 6%).

It is only too easy to see that Grasse did not buck the trend: just look at our post office, for example. But what it did have, around the fringes of the old town, was a plethora of large houses, many with huge gardens, which had been constructed during another building boom. The new technologies of the ‘industrial revolution’ in Grasse from the 1870s up to the Great War made fortunes for perfume families in the same years as the super-rich ‘hivernants’ (winter residents) arrived. The combination drove the development of grand villas on the slopes of the town.

Some still survive, often in multi-occupation, but many of the largest were torn down and their sites re-used. I've selected four of them.

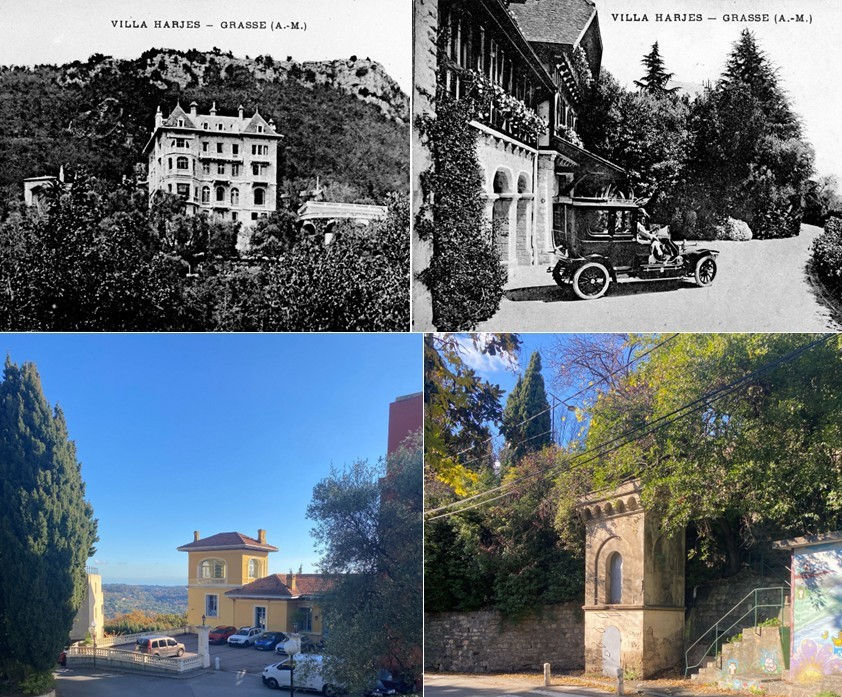

Villa Harjès

John Henry Harjes, who was born in Switzerland but made his fortune as a banker in the USA and France, was typical of the hivernants, although even richer than most of them. His bank, Drexel Harjes, was a lender to the French government after the 1870 war with Prussia. It was strongly affiliated with the JP Morgan bank in the USA, which eventually absorbed it.

John Henry constructed his villa between 1902 and 1905 as his winter home from his main residence in Paris. He didn’t live long to enjoy it, dying in 1914, but the house remained in his family, initially passing to his son, another banker, who was killed in a polo accident in 1926. During the war, it was a German military headquarters which was unsuccessfully bombed by the Americans.

The Harjes were significant benefactors to the American Hospital in Paris, which inherited the villa from John Henry’s estate in 1970 after the death of his grand-daughter. The hospital promptly sold it for development and it’s now a series of residences called Emeraude.

The property covered seven hectares of Grasse’s Malbosc hillside. A contemporary description describes it as “built with beautifully carved stones” and “a work of art that will never be made again”.

Villa des Olivettes

Separated from the Villa Harjès by a deeply incised stream, the Rioucougourde, lay the Villa des Olivettes. The villa was built not by hivernants but by a Grasse family, the Chiris, who were enriched on a major scale by Grasse’s industrial revolution. It was constructed for Georges Chiris, of the fourth generation of the family business, on a six hectare site which is just below the Chateau St Georges – itself erected by Georges’ father Leon and named for him.

When Georges Chiris left – perhaps sometime in the 1930s, it’s not clear from the records available – Villa des Olivettes became first a ‘preventorium’, which means a facility designed to protect the vulnerable, especially children and adolescents, from tubercular diseases. In this it was not too successful, because the owners were prosecuted in 1943. They had admitted some patients who, while no doubt wealthy, were already infected.

In 1954 it was bought and used by the state as a foyer (hostel) and training school for young women, only to be demolished and re-built as a school in the early 1960s. The school was transferred elsewhere in 2003, but its desperately ugly building still exists. Even worse, its stability is in question on its steep site on clay soil. Altogether, it’s difficult to imagine a more chequered history!

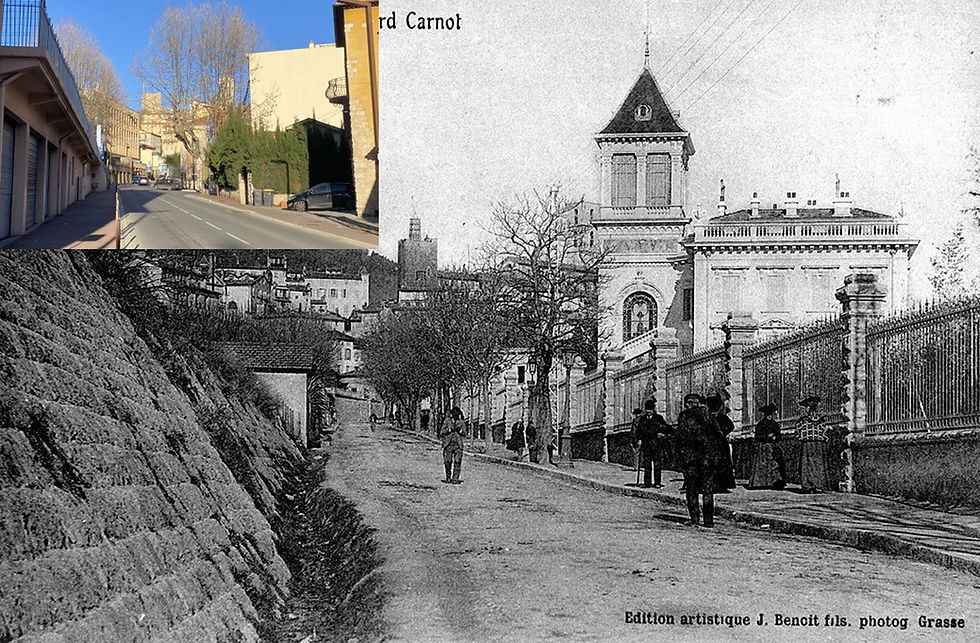

Chateau Isnard

This mansion was built in 1860, just a little before the heyday of both the hivernants and the major perfumiers. It was constructed for Joseph Isnard on the site of a former tannery, just south east of what is now the Cours Honoré Cresp and at the time neighbouring the town's hospital, which was demolished in 1895. Joseph, who was styled a baron, was the grandson of Maximin Isnard, the revolutionary turned imperialist turned royalist whom I have posted about here.

Joseph died in 1901 with no direct descendants and the property passed to a family named Gérard. Seemingly in the early part of the last century, it became apartments, with members of the family living in part of it.

In the 1960s, the town negotiated to buy it, with a view to a development southwards of the Cours which would incorporate a new building. Nothing came of that and the chateau was eventually demolished in 1974. Today’s block is at least slightly more distinguished than Grasse’s many banal blocks of the 1960s and 1970s.

Chateau Roure

The Roure-Bertrand perfume business was Grasse’s second largest (after that of Chiris). It was inherited in 1898 by the fourth generation of the family, two brothers, Louis and Jean, and their sister Marie. Jean left the business under a non-competition agreement with his siblings (much later, he unsuccessfully invested in another perfume concern, Bruno Court) and was richly compensated. So he could well afford the ambitious Art Nouveau house and generous garden which was built for him in around 1900 (his brother Louis had another villa, a little up the road).

It was conveniently situated just outside the old town on the road from the PLM station, but also right next to Grasse’s funicular, which was inaugurated in 1909.

The house was demolished in the early 1960s and its site and garden re-developed.

Villa de Croisset

This was the most spectacular of all. Near to Villas Harjes and des Olivettes, on the road to Magagnosc, was the winter home of one Marie-Thérèse de Chevigné. Her house had been built as the Villa Isabelle in 1885 by John Bowes, an hivernant who was a Liverpool wool dealing millionaire.

Marie-Thérèse bought the mansion because the Grasse climate would be good for the health of her only child from her first marriage, Marie-Laure Bischoffsheim. In 1910, she married her second husband, a Belgian playwright who had changed his birth-name from Franz Wiener to the much grander Francis de Croisset.

One day in 1912, Marie-Thérèse invited to dinner a writer, artist and illustrator named Ferdinand Bac (originally Sigismond-Bach – he was born in Stuttgart). Bac, who had been inspired by a visit to the Ermitage de Saint François (see my post here) in 1908, was not impressed by the Villa Isabelle. He proposed to Marie-Thérèse to transform her “characterless house" and to create a true Mediterranean garden.

Despite Bac’s total lack of experience of building or garden design, she agreed and Bac’s epiphany at St François provoked a new Villa Croisset. His conception was a “pan-Mediterranean style”, with “a series of arcades, courtyards, enclosed gardens, through which one could perceive, in a sweet captivity, the enchantment of a nature”.

When comparing the image of the original Villa Isabelle with one of the Villa Croisset, it's clear that, however 'characterless' Bac thought it, he didn't change much, if anything. But the dream gardens and buildings which he designed and laid out between 1913 and 1922 were extraordinary.

Bac and the Villa Croisset are the subject of a book* recently published by one of our local historians, Christian Zerry.

Unfortunately, it's only available in French, but it tells the story of the villa and its inhabitants and has many illustrations of Bac's designs. Bac went on to design several other gardens, on the Cote d’Azur and elsewhere.

The estate which he created in Grasse was destroyed in 1975 and replaced by apartments. All that remains is a chapel surrounded by what was once a small part of the estate.

The demolition of the Villa des Olivettes was clearly worthwhile, even though its replacement was worse, and the demise of the Chateaux Isnard and Roure regrettable but understandable. But the loss of the gardens of the Villa de Croisset has been described by our local historian André Raspati as 'Le crime de 1975' and it's difficult to disagree.

*Ferdinand Bac sur la Riviera, Christian Zerry, 2024 Éditions Campanile

Comments