Grasse's king of confectioners

- Tom Richardson

- Sep 16, 2025

- 6 min read

Grasse’s famous flower fields traditionally supported not just perfumeries but also confectionery – expertise in extraction was common to both. In 1800, there were over 50 perfume workshops in Grasse and at least seven confectioners. One of them, a Swiss immigrant named Jean Keunig, gave birth to one of Grasse’s most successful family enterprises.

It really began with another immigrant, an Italian named Carlo Negri who was clearly quite an entrepreneur. Carlo came to Grasse from Milan in about 1778 and created a successful carpentry and woodworking business, which he sold in 1814. At some stage, he Frenchified his name to Charles Nègre. He owned a café, constructed buildings and invested in property. In 1818 he bought a building in rue des Suisses jointly with Jean Keunig, most probably that in which Keunig's confectionery business was already established. Carlo passed his share on to his son, Joseph, who learnt the trade of confectionery from M. Keunig and in 1820 bought out his half of the firm (for 4,000 francs, about €20,000 today).

Joseph (1799-1869 ) was an innovator. He developed a product known as ‘confiture de ménage’ (literally ‘household jam') based upon flowers, fruit and lemons which he sold in huge quantities by the standards of the time. According to the 'Crebesc' research website of France’s national guild of artisan bakers and pastry chefs, Joseph also invented ‘sirop de fleur’ (flower-infused syrup) and ‘bonbons acidulés’ (acid drops). The latter seems a little suspicious – the Oxford English Dictionary cites a literary reference to ‘acid drops’ much earlier, in 1783.

His first son, born in 1820, was Charles, the great photographer-artist (see my blog here), but it was his third child, Joseph Adolphe (1828-1923), who carried on the family business.

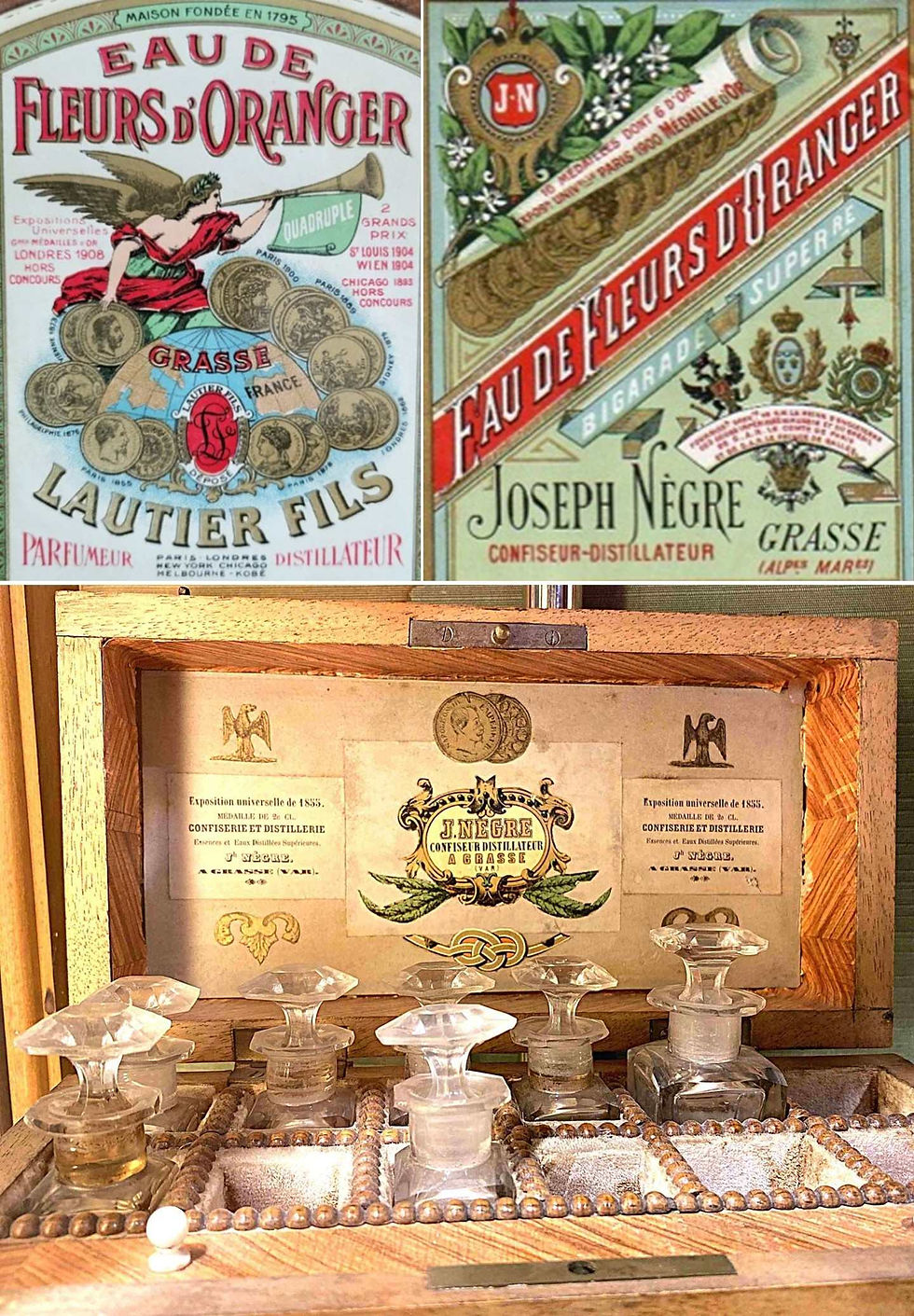

Confectionery and perfumery in Grasse

Perfumers and confectioners shared some processes. Notably, both distilled flowers to make liquids, of which ‘eau de fleurs d’oranger’ (orange blossom water) was perhaps the best known and produced in the highest volume.

It’s not surprising that Emile Litschgy (see my blog here) found that he could transfer his skills from confectionery to perfumery in 1890.

Success and royal endorsement

Crebesc says that by 1850, "all the tea rooms in Cannes offered crystallized or powdered flowers made by Joseph Nègre from red or yellow roses, speckled carnations, Parma violets, pink or mauve lilacs, lavender flowers, etc."

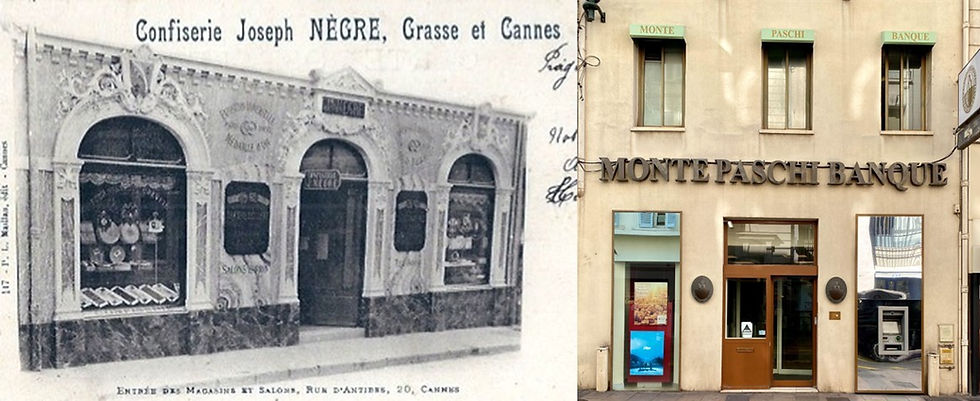

In 1865, Joseph Adolphe opened his own store in Cannes at 20, rue d’Antibes in addition to his Grasse store in rue des Suisses. It is said that customers there "were greeted by a large elephant carrying baskets filled with candied fruit".

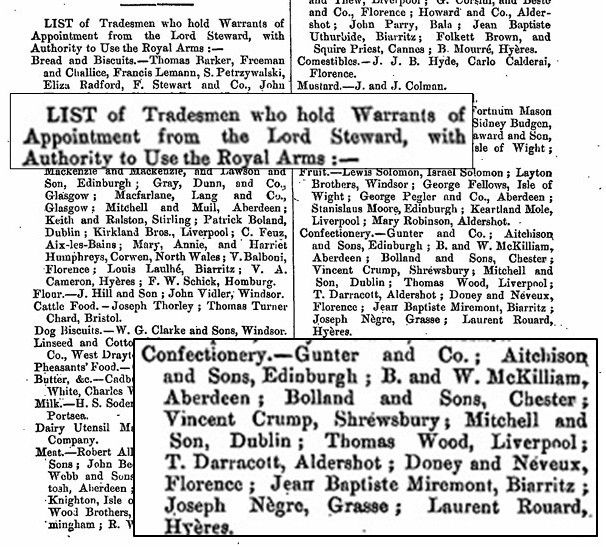

In 1910 a Nice magazine oddly named ‘Pall Mall Illustration’, which claimed to be 'dedicated to the social, sporting, artistic and literary life of the Riviera', said "This house, whose fame is universal, offers an unparalleled choice of gifts at very moderate prices. Everyone knows that Joseph Nègre's signature is the best guarantee of an elegant presentation and unrivalled quality". Perhaps their view was influenced by the business’s being a regular advertiser, but Nègre products were also endorsed by a series of royal warrants, including from the courts of Russia, Brazil, Portugal and Sweden.

Most importantly of all (of course!) Nègre held royal warrants from Queen Victoria and later from KIng Edward VII.

The entry from the London Gazette of 1895 shows that Victoria must have had a sweet tooth – no less than 12 confectioners held her warrant, including establishments in Florence and Hyères as well as Joseph in Grasse. However the inclusion of a confectioner in Biarritz suggests her son Bertie, the future Edward VII, might have had a hand in the selection!

Joseph was said to be "the confiseur des Rois et Roi des confiseurs" ("the confectioner of Kings and King of confectioners").

Rue des Suisses

Apart from a period from 1832 to 1841, when Joseph took premises on the corner of the Place aux Aires and the rue des Fabreries, 16 rue des Suisses was always the centre of the Nègre family's operations. Originally called rue des Imbabaux, it became known as rue des Suisses ('Swiss Street') because several Swiss immigrants, including Jean Keunig, set up businesses there in the early nineteenth century.

As the continuation of Grasse's main rue Droite shopping street, it thrived at least until the Great War, as the postcard below shows.

In the 1890s, it was renamed rue Charles Nègre, after Joseph's eldest son, and now lies behind the Médiatheque which also bears his name.

In 1884, a local directory indicates that there were 10 confectioners and producers of conserves in Grasse. They included Émile Litschgy in the Place aux Herbes and Ernest Keunig, a descendant of Jean, in the Place aux Aires. The Keunig confectionery had been at one time in the Oratoire, the old factory which now houses the Maison de Patrimoine.

In the same year, Joseph Adolphe, who clearly outscaled all of them, had a large new factory built which extended from the rue des Suisses right across to what is now bd Gambetta in the La Roque quarter.

Like the ‘hidden perfumeries’ of my post here, it was converted to apartments after World War II but it’s still prominent along the town’s one way system.

The factory made a huge number of products, including at least twenty varieties of preserved fruit, many types of crystallised and powdered flowers, a wide range of jams and syrups and, by the 1930s, chocolates of all kinds.

Processes included infusing selected flower petals into sugar syrup and drying them to create crystallized petals. Floral syrups were made by infusing petals in sugar solutions, a technique still used today. Fruit was slowly cooked in copper cauldrons to preserve flavour and texture and combined with sugar to create conserves, candied fruit and sweets.

Decline

Still run by the family – another Charles Nègre is identified as a confectioner when a youngish town councillor in 1922 – the business seems to have declined after the Great War. Crebesc blames that on ‘industrial confectionery’, as distinct from the artisanal products made by its members. The Cannes store survived until 1937 and the factory in La Roque a little later.

But it’s still alive in a way…

The creators of the Fragonard brand (see my post here), the Fuchs family, saw continued value in artisanal confectionery as well as in perfumers. In 1935, Émile Fuchs bought the Florian company, which had a chocolate factory in Nice and operated a perfumery in Pont-du-Loup which had once been owned by Grasse's Euzière family.

In 1949, his son Georges purchased the equipment of the old Nègre factory and turned the Pont-du-Loup site into a confectionery which is now the principal Florian site. The confectionery kitchen and its shop is open to visitors, and you can see details here.

Florian’s confectionery is also sold from its sites in Nice, Grasse and Gourdon. Just like that of Joseph Nègre, their range includes sweets, preserved fruits, syrups, jams and candied flowers.

Great article ! Thank you Tom